Warwick Purser’s mission for sustainable welfare in Indonesia - Prestige

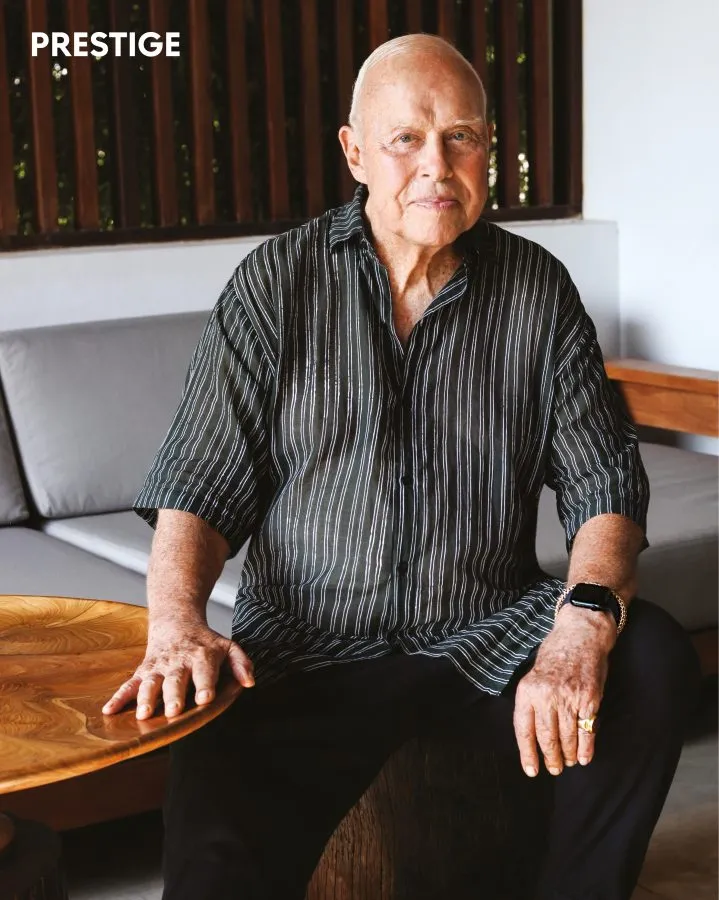

Warwick Purser is a living legend. The Australian-born but now an Indonesian citizen by Presidential decree, is a testament to the power of his humanitarian work within the nation. His journey began many moons ago with setting up “Pacto,” Indonesia’s then-largest travel company. However, due to a governmental policy which stopped allowing foreigners to own companies related to the tourism industry, Warwick, although keeping his home-based in Ubud, Bali, left Indonesia for a while to join United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as a tourism consultant.

Fast forward to a few years later, when in 1993 and his love for Indonesia made him return to the country, where Warwick created “Out of Asia,” a pioneering endeavour that ropelled Indonesian crafts onto the global stage, adorning the shelves of some of the world’s most prestigious retailers. Yet, his mission was more profound, Warwick chose Tembi village as his home, where his mission was to see if rural simplicity could meet commercial ambition. There, he fused a social enterprise within a rural community, weaving a network that benefited everyone.

Two years ago, his undying and enduring love for Indonesian handicrafts led him to establish Omah Budoyo in Yogyakarta. Warwick’s latest venture showcases talents from fashion to culinary to artisans. Visitors have a one-stop experience of what Java, specifically Yogyakarta, have to offer, which has rekindled a passion for Indonesia’s cultural wealth amongst the younger generation. In this exclusive interview with Prestige, Warwick delves into his social enterprises and everything in between.

What does philanthropy mean to you?

For me, philanthropy is not just about giving money, but more importantly, it’s about providing care to people or causes that deserve it, particularly if its advantages can be ongoing. If I look at my history of philanthropy, it’s more based on this care factor than that involving large sums of money. Although, of course, in all cases, as one can expect, money has been involved.

It’s not something you should have to tell people to do. A sense of responsibility is not something you can teach. It has to be something that they feel, and it has to come from the heart. And, of course, that’s not one person’s responsibility to change. We all should have the responsibility to help.

I feel embarrassed talking publicly about philanthropy. Because, in many cases, people should do this anonymously. Because the thing is, you talk about doing it, and then people come back and say, “Oh, aren’t you good? Aren’t those people fortunate?” But no, I believe I’m the fortunate one to have an opportunity to do something like that. It’s me who obtained the rewards.

Do you consider yourself a philanthropist?

First of all, I don’t consider and see myself as a philanthropist. I mean, Bill Gates and Warren Buffet are philanthropists. I consider myself someone who cares about the welfare of other people, but that’s not necessarily in terms of money. Care has to be something that comes from the heart, and I believe it should be ongoing. So, that care for me takes different forms. Put simply, I’m just an Australian-born Indonesian citizen who cares about his country and its fellow citizens.

Photo by Ronald Liem

In the 90s, I started “Out of Asia” in Tembi village, Yogyakarta, because it was a good business opportunity as so few Indonesian craft products were reaching the international market. Its mission was to develop a handcrafted product for export and integrate it into a village community so each could benefit. I did that by allocating part of the profits to build roads, make a kindergarten for village children, and fund the welfare of many families who needed financial assistance. It’s an excellent example of how a commercial enterprise and a village community could cooperate to each other’s advantage.

On this note, it didn’t take long to see where we are working and how the economics of that area could change almost overnight. So, suddenly people had work to do. People returned from the cities to their villages because they suddenly had jobs. The village was paving the streets, repairing houses, and children wore better dress to school. Then, I developed a passion for the handicraft business because I could see how it could change people’s lives.

Unfortunately, the earthquake destroyed my village. So, in conjunction with HSBC, we set up a kitchen that prepared 2,000 meals daily as well as medical centre to feed my village and the whole area. We also set up a fund, brought civil engineers and an architect, and rebuilt the village, ensuring the buildings we did were secure and safe from future natural disasters because we live in an area where natural disasters are occurring all the time.

And then, of course, we had the Merapi eruption in 2010. It covered Borobudur with sulfuric ash, and that was extreme. I went the day after that because I believe Borobudur belongs to all of us, and we are all responsible for ensuring it’s looked after for future generations. At the time, I spoke to the anthropologists there, and they said the money won’t come quickly enough from the government. And they were concerned that the ash would bite into the reliefs and get into the irrigation. So then, in conjunction with UNESCO, I formed a group called “Friends of Borobudur”. And we raised about over a million dollars within a month. So, the work to save Borobudur for future generations could start immediately before government money came through.

I think that it’s something I care about because I’m Indonesian. I’ve been Indonesian for 16 years, which is part of our responsibility. I get so much out of being a citizen of Indonesia that it’s just giving back. And people say, aren’t these people lucky that you do these things? But I think I’m the lucky one because I get so much back.

And in this world, we live in, particularly in the Western world, it’s challenging to make an impression or change. You can significantly change people’s lives in Indonesia with relatively small amounts of money. I live in a village and am conscious that I have a different lifestyle than many people around me. So, I try wherever possible, to help the lives of other people in the village to ensure they always have regular food that comes in every month. But it’s not being generous, it’s not charity for that matter. It’s just giving back to the community that I belong to.

What are you currently prioritising?

Well, if you’re talking about priority, in this case, it’s education for underprivileged families. I’m a Director of the Bali Childrens Foundation (BCF), and we’ve shown how our efforts have increased literacy far above the general literacy level. We’re educating 11,000 children in Bali, Lombok, and soon, Sumba. The importance of giving children a good education is ongoing and BCF is making a real impact.

Another ongoing thing is, of course, where I live in my village, looking after underprivileged people. And that’s being prepared for whatever might happen, including natural disasters. As for Omah Budoyo, I hope it will inspire and motivate the younger generation to love and be proud of local products and learn more about Indonesian culture.

First of all, get out of your base and have a look. You’ve got to take the initiative and see for yourself. Don’t wait for the cause to come to you, you go and find the cause. Then you start to realise what’s needed. And that’s what I try to do as much as possible. That is generally because specific things happen, such as earthquakes or volcanic eruptions. You can’t avoid them because they’re right in your face. And you either have a feeling from your heart that this is something I need to help with or not. In my case, I’ve had that feeling. Because I think in the case of Borobudur, as I said, it belongs to all of us. We all are responsible for it, including the younger generation.

Warwick Purser from his home based d’Omah in Tembi village, Yogyakarta, exemplifies the transformative power of one person’s dedication to the greater good. He is a living testament to the extraordinary change one individual can ignite.